The Great Fowler, Christopher that is. The creator of the magnificent and — err — well-matched duo, Bryant and May.

Suzi Feay, in the current Guardian Review, warns me that:

This month London Bridge Is Falling Down, Fowler’s 20th Bryant & May crime novel, will be published, bringing to a close a much-loved series that started in 2003 with Full Dark House. The books feature the unconventional detective duo Arthur Bryant and John May of London’s Peculiar Crimes Unit, who solve arcane murders whose occult significance baffles more traditional detectives. Crime fiction aficionados can amuse themselves by spotting references to classics of the golden age, whose plots and twists Fowler ingeniously projects on to the era of computers and mobile phones. Everyone else can enjoy the endlessly bantering and discursive dialogue between the pair as they break all procedural rules, and the uniquely droll narrative voice with its sharp-eyed slant on modern life.

Crime fiction is a very crowded genre. Anyone entering the trade has to stretch the envelope. Fowler described that:

When Sir Arthur Conan Doyle conceived Sherlock Holmes, why didn’t he give the famous consulting detective a few more quirks: a wooden leg, say, and an Oedipus complex? Well, Holmes didn’t need many physical tics or personality disorders; the very concept of a consulting detective was still fresh and original in 1887.

Holmes certainly comes with quirks. Each of his successors adds a few more. Fowler, though, tops the list. It is hard to come across any characters so outré as:

John and Arthur, inseparable, locked together by proximity to death, improbable friends for life.

John and Arthur, inseparable, locked together by proximity to death, improbable friends for life.

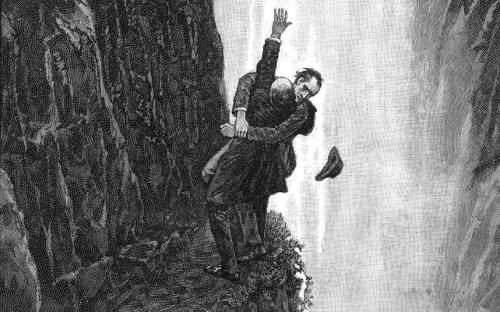

Nor an author who makes as if one of them is killed off on the first page of the first book in the sequence. Even Conan Doyle gave Sherlock twenty-six stories before despatching him (or not, as readers and revenue demanded) down the Reichenbach Falls:

Fowler adds another dimension: the trivia of London geography. In that first outing, he has Bryant and May located in the Palace Theatre, since 1891 that gloomy presence overlooking Cambridge Circus, and now since 2017 haunted by Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. May:

located the theatre archive in a room at the darkest turn in the corridor. Within the cramped suite were dozens of overstuffed boxes and damp cardboard files cataloguing productions and stars. Dim light was provided by the bare bulb overhead. He glanced across the titles on the lids of the boxes and pulled out some of the Palace’s monochrome publicity photographs. Buster Keaton performing with his father, the pair of them bowing to the audience in matching outfits. The jagged profile of Edith Sitwell, posturing her way through some kind of spoken-word concert. A playbill for W. C. Fields starring in a production of David Copperfield. Another presenting him in his first appearance at the Palace as an ‘eccentric juggler’. The four Marx Brothers, gurning for the camera. Fred Astaire starring in The Gay Divorcée, his last show before heading to Hollywood.

The dust on the lower boxes betrayed an even earlier age. The infamous Sarah Bernhardt season of 1892; Oscar Wilde’s Salome was due to have been performed at the theatre, but had fallen foul of the Lord Chamberlain’s ruling about the depiction of religious figures. The legendary Nijinsky, seen onstage just after his split with Diaghilev. According to the notes, he had left the Palace after discovering that he was to appear at the top of a common variety bill. Cicely Courtneidge in a creaky musical comedy, her dinner-jacketed suitors arranged about her like Selfridge’s mannequins. The first royal command performance, in 1912. Anna Pavlova dancing to Debussy. Max Miller in his ludicrous floral suit, pointing cheekily into the audience—’You know what I mean, don’t you, missus?’ Forgotten performers, the laughter of ghosts.

Counting those lately missing in action: Henning Mankell, Colin Dexter, Sue Grafton, Philip Kerr, John le Carré …