[Your constant reminder this is a port from Malcolm Redfellow’s Home Service, because WordPress doesn’t like Safari browsers.]

At its best, a book tells at least two stories: the text within, and the metatext that surrounds what is within.

Here’s an example:

14. JB Priestley, English Journey

My copy lacks this wrap-around dust-cover, which would multiply its monetary value several fold. It is, nevertheless, a first edition, and in remarkable condition for an octogenarian.

Inside the front cover, its first owner has inscribed, in respectfully modest minuscule, ‘H. Barnett. 23 July 1934’. Below which, in an educated, even artistic hand, larger, more confident, ‘CT’ (or possibly ‘GT’) ‘1988’, forcibly underlined. In the corner above, Oxfam Books (where I bought it) has pencilled ‘£2,99, w 13’. There’s a whole history summarised.

I obviously got a bargain, because opposite in in delicate pencil is ‘1934 £7.50 1st edition’.

Over the year I have picked up some remarkable autographs in such inscriptions. At one stage I was collecting Left Book Club editions, and found I had the names of a couple of Cabinet members from the Attlee years. The Pert Young Piece rescued those when we moved house, and squealed with delight at her discoveries. One never knows until one looks.

We could, pertinently, ask why Priestley’s text has survived and prospered.

First of all, it was to Priestley and now to us a voyage of exploration, historical and personal.

Start with the extended subtitle:

Being a rambling but truthful account of what one man saw and heard and felt during a journey through England during the autumn of the year 1933

— precise, subjective and emotive (at least in the sense it is placed definitively within Priestley’s own personal emotions).

That comes through with one of his first trips, to Southampton:

I had been to Southampton before, many times, but always to or from a ship. The last time I sailed for France during the war was from there, in 1918, when half a dozen of us found ourselves the only English officers in a tall crazy American ship bursting with doughboys, whose bands played ragtime on the top deck. Since then I had sailed for the Mediterranean and New York from Southampton, and had arrived there from Quebec. But it had no existence in my mind as a real town, where you could buy and sell and bring up children; it existed only as a muddle of railway sidings, level crossings, customs houses and dock sheds: something to have done with as soon as possible. The place I rolled into down the London Road was quite different, a real town.

Margin Released (1962) was as close as Priestley came to a memoir, and beyond the second section and a few letters from the trenches we have to piece together his WW1 service. He had volunteered on 7 September 1914. He was posted to France as a lance-corporal in the 10th Battalion, was wounded twice, most seriously being buried by a trench mortar in June 1916 (which required an extended convalescence). At the dog-end of the War he was back as an officer (anyone of any capability who had lasted four years was likely to be advanced that far) and may have suffered a slight gassing.

In English Journey, he returns to the West Riding, and Bradford, invited to a regimental reunion:

I should not be writing this book now if thousands of better men had not been killed; and if they had been alive still, it is certain that I should have been writing, if at all, about another and better England. I have had playmates, I have had companions, but all, all arc gone; and they were killed by greed and muddle and monstrous cross-purposes, by old men gobbling and roaring in clubs, by diplomats working underground like monocled moles, by journalists wanting a good story, by hysterical women waving flags, by grumbling debenture-holders, by strong silent be-ribboned asses by fear or apathy or downright lack of imagination. I saw a certain War Memorial not long ago; and it was a fine obelisk, carefully flood-lit after dark. On one side it said Their Name Liveth For Evermore and on the other side it said Lest We Forget. The same old muddle, you see: reaching down to the very grave, the mouldering bones. I was with this battalion when it was first formed, when I was a private just turned twenty; but 1 left it, as a casualty, in the summer of 1916 and never saw it again, being afterwards transferred to another regiment. The very secretary who wrote asking me to attend this dinner was unknown to me, having joined the battalion after I had left it. So I did not expect to see many there who had belonged to the old original lot, because I knew only too well that a large number of them, some of them my friends, had been killed. But the thought of meeting again the few I would remember, the men who had shared with me those training camps in 1914 and the first half of 1915 and those trenches in the autumn and winter of 1915 and the spring of 1916, was very exciting. There were bound to be a few there from my old platoon, Number Eight. It was a platoon with a character of its own. Though there were some of us in it young and tender enough, the majority of the Number Eighters were rather older and grimmer than the run of men in the battalion; tough factory hands, some of them of Irish descent, not without previous military service, generally in the old militia. When the battalion was swaggering along, you could not get Eight Platoon to sing: it marched in grim, disapproving silence. But there came a famous occasion when the rest of the battalion, exhausted and blindly limping along, had not a note left in it; gone now were the boasts about returning to Tipperary, the loud enquiries about the Lady Friend; the battalion was whacked and dumb. It was then that a strange sound was heard from the stumbling ranks of B Company, a sound never caught before; not very melodious perhaps nor light-hearted, but miraculous: Number Eight Platoon was singing. Well, that was my old platoon, and I was eagerly looking forward to seeing a few old remaining members of it. But I knew that I should not see the very ones who had been closest to me in friendship, for they had been killed; though there was a moment, I think, when I told myself simply that I was going to see the old platoon, and, forgetting the cruelty of life, innocently hoped they would all be there, the dead as well as the living.

After rambling (quite literally) up the Dales, Priestley heads for the Potteries and then to Liverpool and Lancashire. This is where the tone of the Journey changes, and Priestley’s mood with it. What about the slums of Liverpool? —

A great many speeches have been made and books written on the subject of what England has done to Ireland. I should be interested to hear a speech and read a book or two on the subject of what Ireland has done to England. If we do have an Irish Republic as our neighbour, and it is found possible to return her exiled citizens, what a grand clearance there will be in all the Western ports, from the Clyde to Cardiff what a fine exit of ignorance and dirt and drunkenness and disease. The Irishman in Ireland may, as we are so often assured he is, be the best fellow in the world, only waiting to say good-bye to the hateful Empire so that, free and independent at last, he can astonish the world. But the Irishman in England too often cuts a very miserable figure. He has lost his peasant virtues, whatever they are, and has acquired no others. These Irish flocked over here to be navvies and dock hands and casual labourers, and God knows that the conditions of life for such folk are bad enough. But the English of this class generally make some attempt to live as decently as they can under these conditions: their existence has been turned into an obstacle race, with the most monstrous and gigantic obstacles, but you may see them straining and panting, still in the race. From such glimpses as I have had, however, the Irish appear in general never even to have tried; they have settled in the nearest poor quarter and turned it into a slum, or, finding a slum, have promptly settled down to out-slum it. And this, in spite of the fact that nowadays being an Irish Roman Catholic is more likely to find a man a job than to keep him out of one. There are a very large number of them in Liverpool, and though I suppose there was a time when the city encouraged them to settle in it, probably to supply cheap labour, I imagine Liverpool would be glad to be rid of them now. After the briefest exploration of its Irish slums, I began to think that Hercules himself will have to be brought back and appointed Minister of Health before they will be properly cleaned up, though a seductive call or two from de Valera, across the Irish Sea, might help. But he will never whistle back these bedraggled wild geese. He believes in Sinn Fein for Ireland not England.

Tsk! Tsk! Mr Priestley!

If Priestley is out-of-sorts in Liverpool, his temper worsens as he drives through industrial Lancashire:

We went through Bolton. Between Manchester and Bolton the ugliness is so complete that it is almost exhilarating. It challenges you to live there. That is probably the secret of the Lancashire working folk: they have accepted that challenge; they are on active service, and so, like the front-line troops, they make a lot of little jokes and sing comic songs. There used to be a grim Lancashire adage: “Where there’s muck, there’s money.” But now when there is not much money, there is still a lot of muck. It must last longer. Between Bolton and Preston you leave the trams and fried-fish shops and dingy pubs; the land rises, and you catch glimpses of rough moorland. The sun was never visible that afternoon, which was misty and wettish, so that everything was rather vague, especially on the high ground. The moors might have been Arctic tundras. The feature of this route, once you were outside the larger towns, seemed to me to be what we call in the North the “hen runs.” There were miles of them. The whole of Lancashire appeared to be keeping poultry. If the cotton trade should decline into a minor industry, it looks as if the trains that once carried calico will soon be loaded with eggs and chickens. It is, of course, the extension of what was once a mere hobby. Domestic fowls have always had a fascination for the North-country mill hands. It is not simply because they might be profitable; there is more than that in it. The hen herself, I suspect, made a deep sub-conscious appeal to these men newly let loose from the roaring machinery. At the sound of her innocent squawking, the buried countryman in them began to stir and waken. By way of poultry he returned to the land, though the land he had may have been only a few square yards of cindery waste ground. Now, of course, sheer necessity plays its part too. We were going through the country of the dole.

He is back, eighty years on, in Dickens’s Coketown. Preston, which is generally taken as the model for ‘Coketown’, shows the cotton trade already in terminal decline:

That very day a mill, a fine big building that had cost a hundred thousand pounds or so not twenty years ago, was put up for auction, with no reserve: there was not a single bid. There hardly ever is. You can have a mill rent-free up there, if you are prepared to work it. Nobody has any money to buy, rent or run mills any more.

George Orwell will follow a couple of years later, also on Victor Gollancz’s money and patronage, and do a better, more incisive demolition.

That followed quickly by an anticipation of the North-South divide, the ‘Red Wall’, ‘levelling up’ and other false promises:

Lancashire must have a big plan. What is the use of England — and England in this connection, of course, means the City, Fleet Street, and the West End clubs — congratulating herself upon having pulled through yet once again, when there is no plan for Lancashire. Since when did Lancashire cease to be a part of England? […] No man can walk about these towns, the Cinderellas in the baronial household of Victorian England, towns meant to work in and not to live in and now even robbed of their work, without feeling that there is a terrible lack of direction and leadership in our affairs. It does not matter now whether Manchester does the thinking to-day and the rest of England thinks it to-morrow, or whether we turn the tables on them and think to-day for Manchester to-morrow. But somebody somewhere will have to do some hard thinking soon.

And on this most unsatisfactory conclusion, asking myself, over and over again, what must be done with these good workless folk, I took leave […] and made for the bleak and streaming Pennines, on my way to the Tyne; with the weather, like my journey, going from bad to worse.

By which time Priestley is running a cold and a temperature, and dislikes Newcastle :

taking a great dislike to the whole district, which seemed to me so ugly that it made the West Riding towns look like inland resorts.

Then he anticipates Orwell precisely:

On a morning entangled in light mist, under a sullen sky, I left the Tyne by road for East Durham. Most of us have often crossed this county of Durham, to and from Scotland. We are well acquainted with the fine grim aspect of the city of Durham, with that baleful dark bulk of castle, which at a distance makes the city look like some place in a Gothic tale of blood and terror. […] It is, you see, a coalmining district. Unless we happen to be connected in some way with a colliery, we do not know these districts. They are usually unpleasant and rather remote and so we leave them alone. Of the millions in London, how many have ever spent half an hour in a mining village? How many newspaper proprietors, newspaper editors, newspaper readers have ever had ten minutes’ talk with a miner? How many Members of Parliament could give even the roughest description of the organisation and working of a coal-mine? How many voters could answer the simplest questions about the hours of work and average earnings of a miner? These are not idle queries. I wish they were. If they had been, England would have been much merrier than it is now.

Most English people know as little about coal-mining as they do about diamond-mining. Probably less, because they may have been sufficiently interested to learn a little about so romantic a trade as diamond-mining. Who wants to know about coal? Who wants to know anything about miners, except when an explosion kills or entombs a few of them and they become news?

His journey returns him south: he isn’t much taken by York, quite likes Beverley, and finds Hull busy with fish and grain:

It remains in my memory as a sound and sensible city, not at all glamorous in itself yet never far from romance, with Hanseatic League towns and icebergs and the Northern Lights only just round the corner.

Lincoln he likes, too: a comfortable hotel, some companionship, and

few things in this island are so breathlessly impressive as Lincoln Cathedral, nobly crowning its hill, seen from below. It offers one of the Pisgah sights of England. There, it seems, gleaming in the sun, are the very ramparts of Heaven. That east wind, however, blew all thoughts of idling in the Minster Yard out of my mind.

Ditto market day in Boston, and not quite three hundred feet high Boston Stump (actually, St Botolph’s is just over eighty metres).

And so via King’s Lynn to Norwich:

1 was not paying my first visit to Norwich, though I had never stayed there before. But I must have lunched several times at the Maid’s Head, and then spent an hour looking at the antique shops in Tombland. The last time we were there, I remembered, we had bought a John Sell Cotman and a pretty set of syllabub glasses.

For me the notion of finding a Cotman in an antique shop, is more than anything else the distinction of 1934 and today. Priestley then chucks in an anticipation of regional government:

What a grand, higgledy-piggledy, sensible old place Norwich is! May it become once more a literary and publishing centre, the seat of a fine school of painters, a city in which foreigners exiled by intolerance may seek refuge and turn their sons into sturdy and cheerful East Anglians; and may I live to sec the senators of the Eastern Province, stout men who take mustard with their beef and beer with their mustard, march through Tombland to assemble in their capital.

Bring it on, say I.

Finally his journey over, Priestley works up a froth to sum it all. We then see why he became so popular during the Second Unpleasantness (1939-1945). The Central Office of Information decided that regional voices were a good thing — apart from much else, they were harder for the Huns to imitate, and they did give some sense of ‘We’re all in this together’. Despite Priestley’s boast of keeping his Bradford accent, three years at Cambridge had softened it. In his war-time broadcasts he reconstructs it (as did John Arlott, Wilfred Pickles, and others).

In 1934 ‘Jack’ Priestley is already preparing himself for that rôle (he was ever a man of the theatre):

I thought about patriotism. I wished I had been born early enough to have been called a Little Englander, It was a term of sneering abuse, but 1 should be delighted to accept it as a description of myself. That little sounds the right note of affection. It is little England I love. And I considered how much I disliked Big Englanders, whom I saw as red-faced, staring, loud-voiced fellows, wanting to go and boss everybody about all over the world, and being surprised and pained and saying, “Bad show!” if some blighters refused to fag for them. They are patriots to a man. I wish their patriotism began at home, so that they would say — as I believe most of them would, if they only took the trouble to go and look — “Bad show!” to Jarrow and Hcbburn. After all, I thought, I am a bit of a patriot too. I shall never be one of those grand cosmopolitan authors who have to do three chapters in a special village in Southern Spain and then the next three in another special place in the neighbourhood of Vienna. Not until I am safely back in England do I ever feel that the world is quite sane. (Though I am not always sure even then.) Never once have I arrived in a foreign country and cried, ‘This is the place for me.” I would rather spend a holiday in Tuscany than in the Black Country,, but if I were compelled to chose between living in West Bromwich or Florence, I should make straight for West Bromwich.

Decode that ‘metatext’.

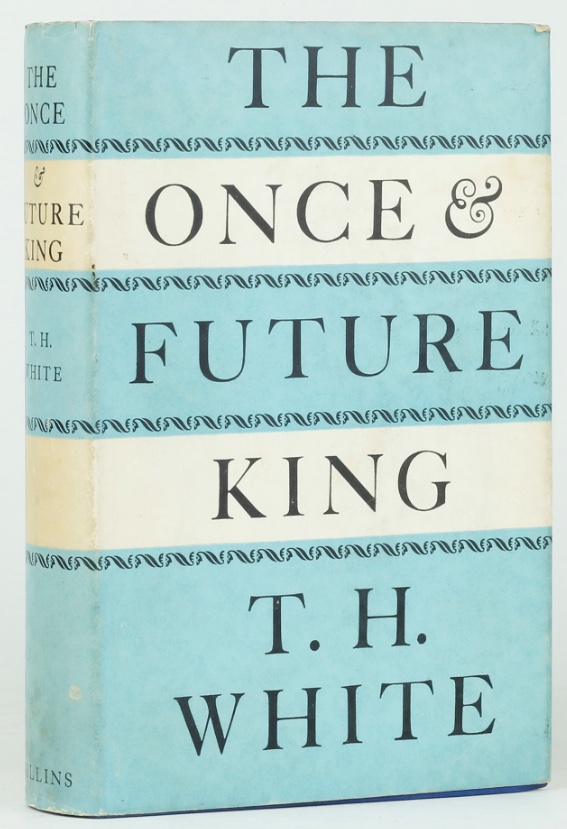

The day finally came when I felt the juvenilia no longer provided. I turned to the back end, S-Z, of the adult fiction shelves. And plucked out White, fresh from the press and a first-edition.

The day finally came when I felt the juvenilia no longer provided. I turned to the back end, S-Z, of the adult fiction shelves. And plucked out White, fresh from the press and a first-edition.